|

Often, we don’t think twice about the food in our fridge, but for some Canadians, especially those who identify as Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour (BIPOC), this is not the case. Food insecurity is characterised by concerns of running out of food, nutrient inadequacies, and in severe cases, not eating for several whole days. Unfortunately, BIPOC communities have a significantly higher chance of facing household food insecurity mainly due to a lower average income. This income issue is a direct consequence of deeply ingrained systemic racism. Policies reflecting systemic colonialism continue to advantage white people, leading to racial inequities in all aspects of life for the BIPOC community.

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

|

The disparity between white and BIPOC households when it comes to food security has been a lasting issue in Canada. 1 in 8 Canadian households, amounting to over 4 million people, struggle with food insecurity on a daily basis. Among this population, there is a disproportionate number of BIPOC households. The COVID-19 pandemic has only compounded the existing inequities in these marginalized communities.

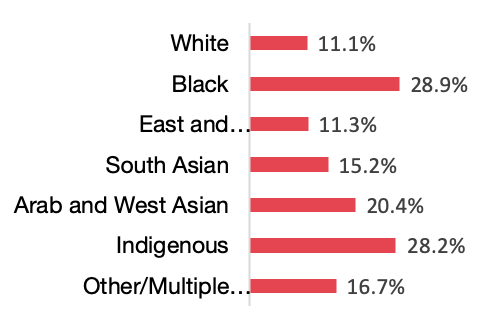

Prevalence of household food insecurity in relation to racial/cultural identity and Indigenous status. Reproduced from "Household Food Insecurity in Canada," PROOF: Food Insecurity Policy Research.

|

Food insecurity rates are highest in Nunavut, where Indigenous households make up the majority of the population. Across Canada, 28.2% of Indigenous households and 28.9% of Black households are food insecure, while only 11.1% of white households are food insecure. Black Canadians and Indigenous peoples are significantly more likely to face food insecurity compared to white Canadians, even when accounting for factors like homeownership, income, and education levels.

Trends in Household Food Insecurity

There are many factors to account for when examining food insecurity in BIPOC households. Contributing factors for greater food insecurity include, but are not limited to:

- Low wages and Unemployment – One of the major reasons for food insecurity within BIPOC households is the enduring and prevailing racial income inequality. Tarasuk (2020) found that food insecurity affects 60.4% of households relying on social assistance, a demographic mainly consisting of the BIPOC community. Similarly, a publication by the Metcalf Foundation found that the largest group of the working poor, a class of working citizens that fall below the poverty line, in Toronto consists of racialized individuals. Namely, Black females, Black males, and South Asian Males. Families that are dealing with financial problems are likely to have little money left to spend on food after they pay their mortgage or rent.

Race – Low-income white households experience certain levels of food insecurity as well, but there are privileges inherent to their race that allow them to bounce back in ways that BIPOC households cannot. A research collaboration between PROOF and Food Share (2019) has shown that race is an overwhelming predictor of food insecurity. Within the Canadian population, Black and Indigenous households are at the greatest risk of food insecurity.

- Housing – Homeownership greatly protects against food insecurity. However, this privilege differs by race. According to Tarasuk (2020), 61% of food-insecure households are renting their home. A slight increase in the minimum wage in recent years is not enough to offset the rising rental costs in many neighbourhoods and cities such as Toronto.

Photo by Tierra Mallorca on Unsplash

|

- Education – There is an evident connection between education and household food security. The quality of education that you receive predicts how much you are going to earn. The structural barriers and lack of equal opportunities when it comes to education between white and BIPOC Canadians is a direct contributor to the food insecurity problem.

Household food insecurity compromises the health and wellbeing of those affected. Deeply embedded racial biases and policies continue to persist and affect BIPOC households across Canada. Understanding the roots of food insecurity allows us to tackle this issue on all fronts.

Supporting Articles:

- Dhunna, S., and Tarasuk, V. (2019). Fact Sheet: Race and Food Insecurity. Proof and FoodShare. https://foodshare.net/custom/uploads/2019/11/PROOF_factsheet_press_FINAL.6.pdf

- Roberts, Melana. (2020, February 3). Black Food Insecurity in Canada. Broadbent Institute. www.broadbentinstitute.ca/Black_food_insecurity_in_canada

- Stapleton, J. (2019). The Working Poor in the Toronto Region: A closer look at the increasing numbers. Metcalf Foundation. https://metcalffoundation.com/site/uploads/2019/11/Working-Poor-2019-NEW.pdf

- Suga, H. (2018). Household Food Unavailability Due to Financial Constraints Affects the Nutrient Intake of Children. European Journal of Public Health, 29(5), 816-820. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cky263

- Tarasuk V, and Mitchell A. (2020) Household food insecurity in Canada, 2017-18. Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF). https://proof.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Household-Food-Insecurity-in-Canada-2017-2018-Full-Reportpdf.pdf

|